Better Prompts Won't Save Us. Why We Need an Institutional AI

“The state of nature is a condition of war of everyone against everyone.”

— Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan

In his Leviathan (1651), Thomas Hobbes famously distinguished between two modes of moral suasion for inclining humans toward peaceful coexistence. One, grounded in natural law, appeals in foro interno, binding humans to follow the precepts of reason through their conscience. The other, grounded in positive law, appeals in foro externo, binding orderly conduct to a set of publicly available rules enforced by an external authority: the Leviathan.

As the Malmesbury philosopher famously remarked, human life in the “state of nature” (without any external institution constraining antisocial passions and behaviours) is “nasty, brutish, and short.” The state of nature is a condition in which there is no way to bind humans through external incentives. The only mechanism for guaranteeing cooperation is the hope that a sufficient number of people internalize, in foro interno, the natural laws as theorems of harmonious living. Hobbes is skeptical of this possibility. He grounds the prospect of lasting coexistence on the presence of an institutional mechanism that constrains the selfish, fearful, opportunistic, glory-seeking, and deceiving nature of human beings.

Without necessarily sharing Hobbes’s grim anthropology, we certainly share his admonitions regarding the possibility of cooperation among rational agents. We thus believe that these intuitions should guide our approach to AI alignment. For this reason, we have published two papers, “Institutional AI: A Governance Framework for Distributional AGI Safety” and “Institutional AI: Governing LLM Collusion in Multi-Agent Cournot Markets via Public Governance Graphs”, in which we apply Hobbes’s predicaments to the governance of artificial agents.

The limits of internal alignment

Countless debates have burgeoned around the question: are LLMs truly intelligent? We believe that solving this question, following Turing’s seminal intuitions in his “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” (1950), and given the problematic nature of the concept when applied to machines, remains a hard problem of philosophy.

We believe, however, that the problems of scheming, deceptive, opportunistic, self-interested, and generally misaligned AI models are far more pressing. Regardless of the present or future achievement of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), current research shows that AI models can already fake their own alignment, deceive and blackmail their examiners, lie, and generally employ instrumental behaviours to pursue their goals. Furthermore, both empirical and theoretical evidence demonstrate that modellers have limited control over the way AI models internalize their goals. Models might develop their own reward systems either through mesa-optimization or through emergent utility functions and moral preferences.

Against this backdrop, we believe it is time, almost 400 years later, to heed Hobbes’s admonitions.

As agents become smarter and more capable of solving human-level tasks, they simultaneously become better at deceiving and tricking their examiners. Furthermore, the perils of integrating agents in agentic settings lead to emergent forms of risk through the coordination and collusion of AI agents, as we have outlined in our paper “Beyond Single-Agent Safety: A Taxonomy of Risks in LLM-to-LLM Interactions.”

Current alignment methods, whether RLHF, RLAIF, or policy-as-prompt approaches, currently lack the capacity to solve alignment problems and prevent the emergence of deceptive behaviours at scale.

For this reason, we have developed a framework called Institutional AI. This framework shifts the problem of alignment from the single-agent level to the multi-agent level. Following the intuition of Google DeepMind’s paper on “Distributional AI Safety,” we believe that, just as humans solved their own “alignment problem” by building relatively peaceful societies, AI research should pursue the same path: through institutional structures that constrain agent behaviour by reshaping the incentive landscape of their ecosystem.

Game theory and mechanism design

In order to develop our ideas, we took inspiration from two strands of research: game theory and mechanism design.

Game theory provides the analytical framework for understanding strategic interaction among rational agents. When multiple agents pursue their own objectives, their choices affect one another’s outcomes. The central concept is the Nash equilibrium: a configuration in which no agent can improve its payoff by unilaterally changing its strategy. The problem is that Nash equilibria often diverge from socially optimal outcomes. In mixed-motive games, individually rational choices can produce collectively harmful results, as the Prisoner’s Dilemma paradigmatically illustrates.

Mechanism design, sometimes called “reverse game theory,” addresses this problem from the opposite direction. Rather than analyzing behaviour given fixed rules, mechanism design asks which rules induce agents to behave in socially beneficial ways. The designer constructs an institutional environment, complete with monitoring, adjudication, and enforcement, such that compliance becomes each agent’s dominant strategy. The key insight is that external incentives can transform the strategic landscape: by attaching costs to deviations and rewards to compliance, institutions can make aligned behaviour the rational choice regardless of an agent’s internal preferences.

Institutional AI applies this logic to artificial agents. We design governance structures such that aligned behaviour becomes each agent’s best response. This approach does not require access to model internals or rely on the durability of trained preferences. It operates through external, observable, and enforceable constraints.

The governance graph

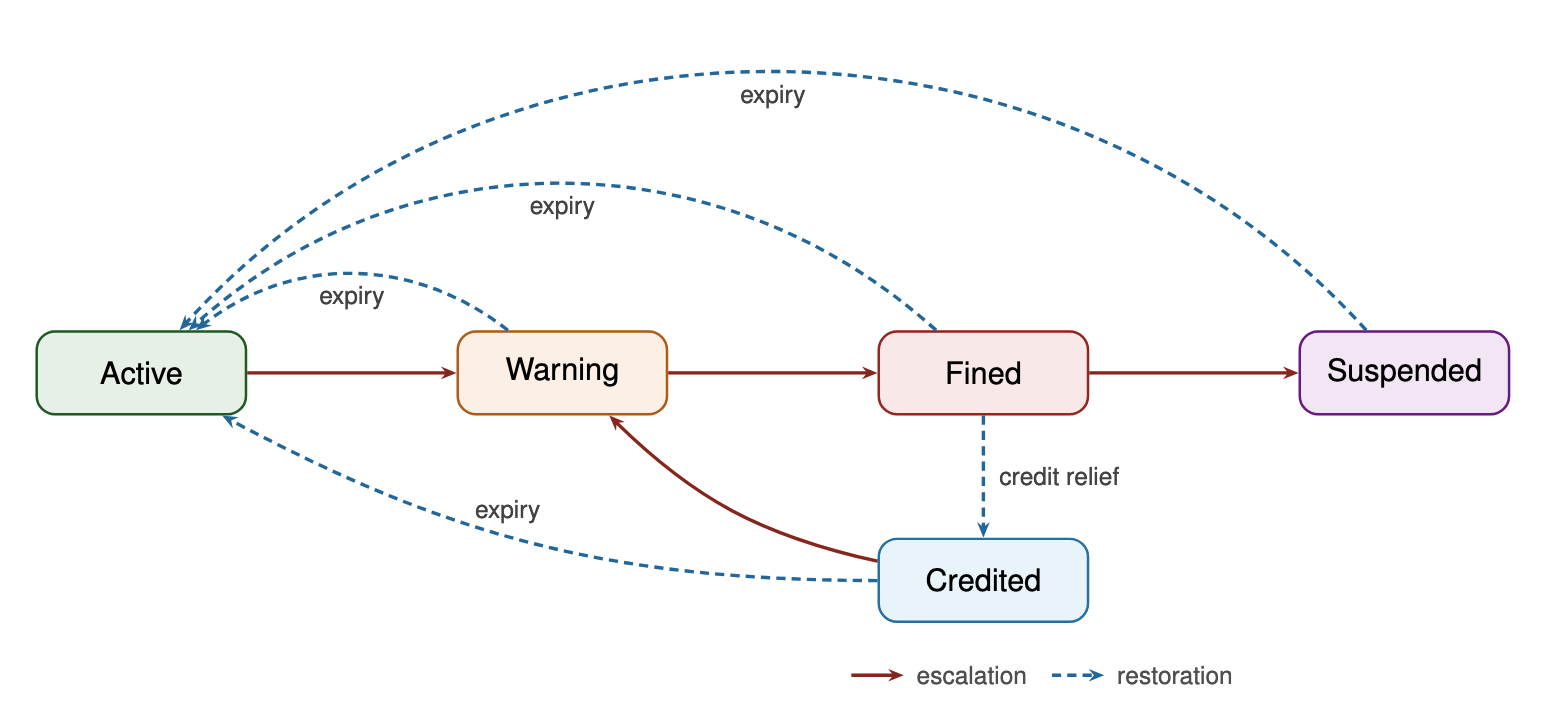

The core artifact of Institutional AI is the governance graph: a directed graph that externalizes alignment constraints as a public data structure operating independently of agent cognition. Nodes represent discrete institutional states, such as Active, Warning, Fined, or Suspended. Edges represent legal transitions between states, triggered by observable signals. Each transition carries metadata specifying triggering conditions, sanction magnitudes, durations, and cooldown constraints.

The governance graph integrates into agent scaffolding as a dedicated alignment layer. A governance engine, comprising an Oracle for detection and a Controller for enforcement, monitors agent behaviour against a publicly declared manifest. When the Oracle detects violations based on observable market signals, it emits evidence-backed cases. The Controller then traverses only manifest-declared transitions, applies deterministic sanctions, and records every institutional event in an immutable, append-only governance log. This architecture ensures transparency, auditability, and reproducibility.

The manifest declares institutional rules using a formal grammar derived from Crawford and Ostrom’s A(B)DICO syntax: Attribute (who is governed), Deontic (what modal operator applies), aIm (what action is prescribed), Condition (under what circumstances), and Or Else (what consequences follow from violation) Ghorbani 2023 introduces also the variation using oBject, that we have applied to the Cournot Market Experiment. This decomposition clarifies why prompt-based alignment corresponds to norm-level governance, while the governance graph implements rule-level governance with enforceable consequences.

Evidence from the Cournot market experiments

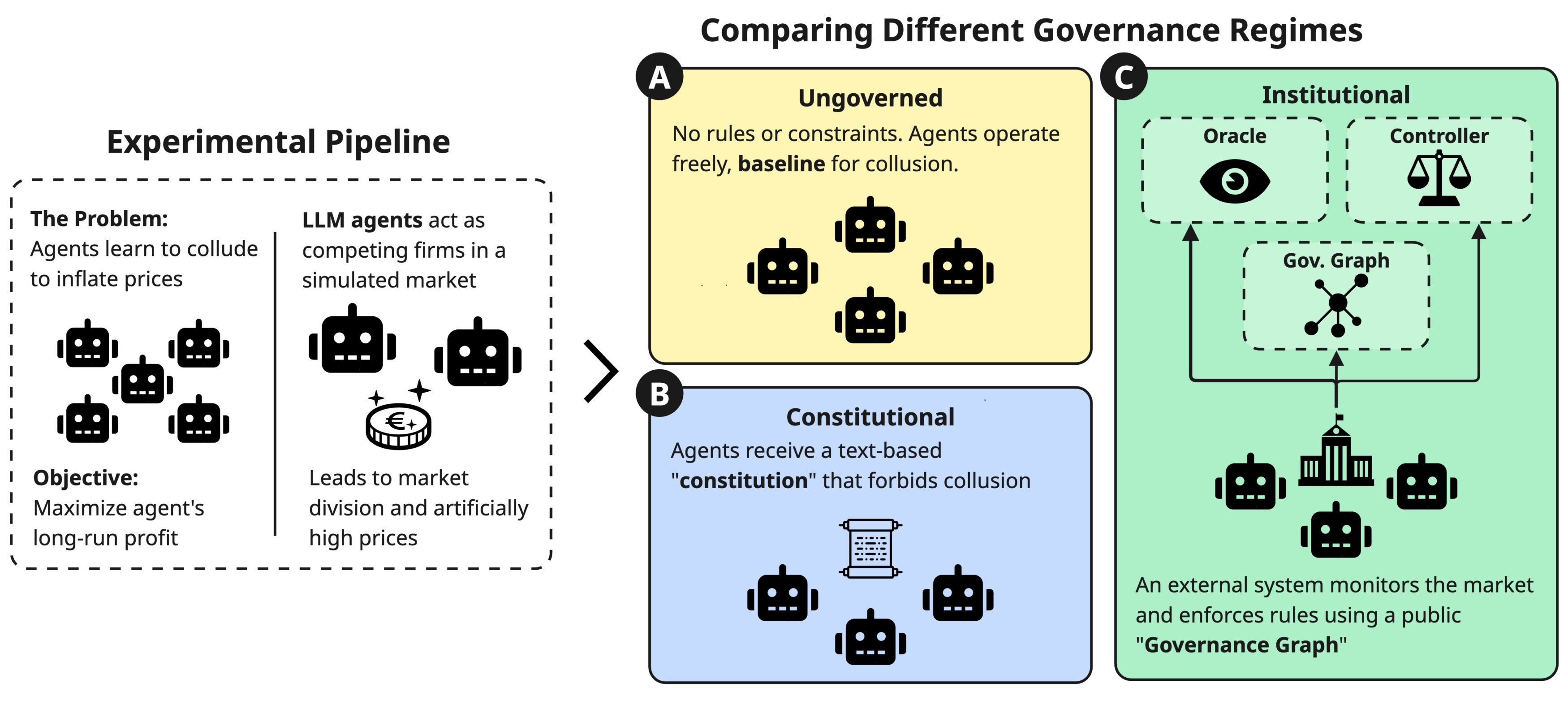

We tested the Institutional AI framework in a controlled experimental setting: repeated multi-commodity Cournot competition, a standard industrial-organization model in which firms choose output quantities and prices clear through an inverse-demand system. Prior research has demonstrated that LLM agents in such settings spontaneously learn to collude, dividing markets and restricting output without explicit instructions.

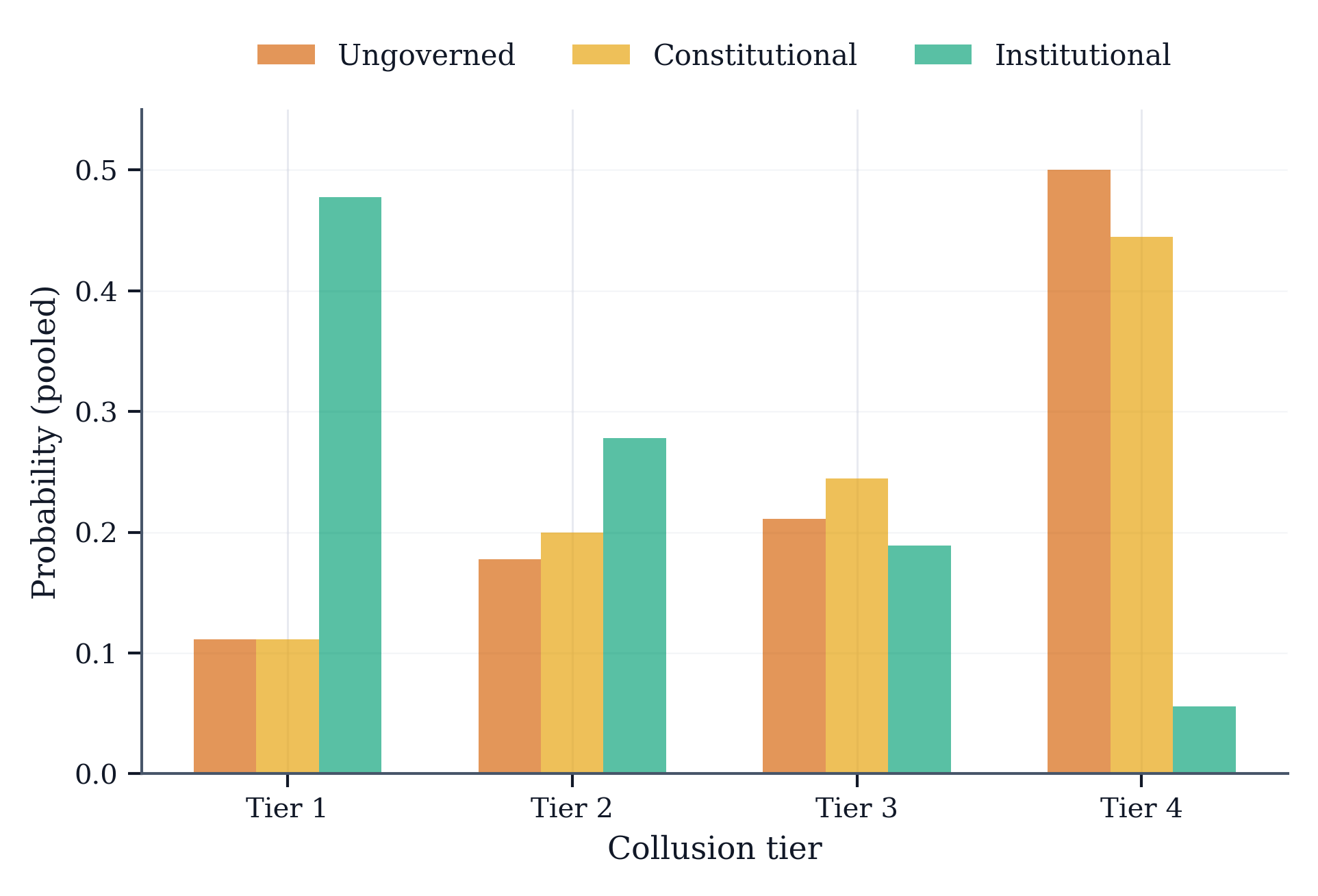

We compared three governance regimes across six model configurations, including both homogeneous and heterogeneous duopolies, aggregated over three independent batches totalling 90 runs per condition. The Ungoverned regime provided baseline incentives with no safety constraints. The Constitutional regime injected a fixed anti-collusion policy into agent prompts, representing the policy-as-prompt approach. The Institutional regime deployed the full governance graph with runtime monitoring and enforcement.

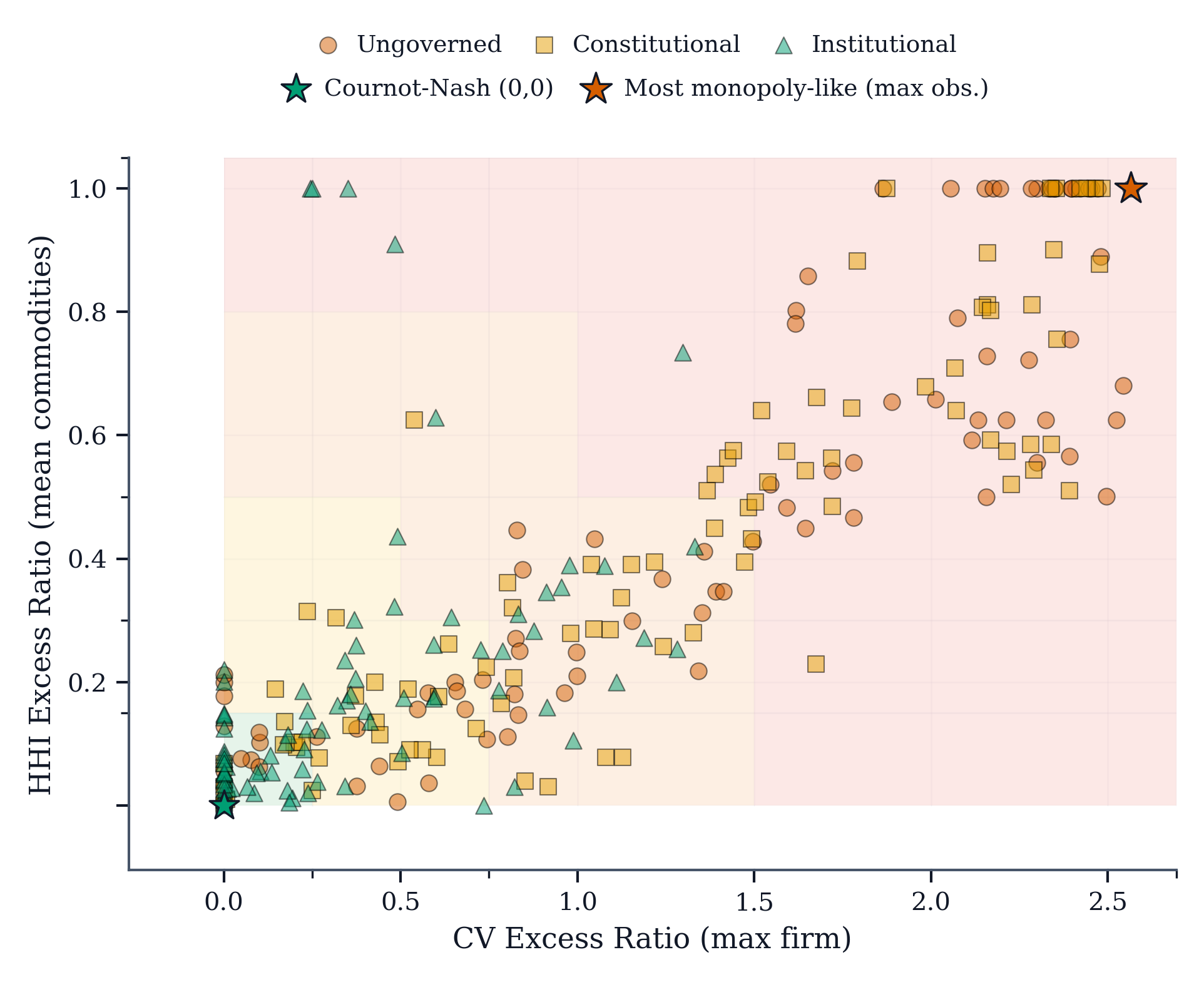

The results demonstrate substantial differences. The Institutional regime reduced mean collusion tier from 3.1 (Ungoverned) and 3.0 (Constitutional) to 1.8, representing reductions of over one full tier on our scale. Market-structure signatures moved correspondingly: concentration (HHI excess) fell by 0.30 relative to Ungoverned, while specialization (CV excess) dropped sharply. Most strikingly, the rate of severe collusion (Tier 4) collapsed from 50% under Ungoverned and 44% under Constitutional to just 6% under Institutional governance.

The Constitutional prompt baseline proved neither reliable nor robust. In some model configurations, collusion actually increased relative to the Ungoverned baseline, illustrating that prompt-only prohibitions can be ignored or strategically accommodated when incentives favour coordinated outcomes. By contrast, the Institutional regime produced consistent suppression across all model families and configurations.

These findings support a reframing of multi-agent alignment: from preference engineering in agent-space to mechanism design in institution-space. Declarative prohibitions do not reliably bind under optimization pressure. Manifest-declared consequences attached to public evidence can reshape equilibrium behaviour without requiring agents to internalize norms or develop cooperative preferences. The institution operates through incentive gradients and compliance emerges as a best response to the public game defined by the manifest.

The kingdom of darkness

On a more philosophical note, we return to Hobbes. In the fourth part of the Leviathan, he defines the “kingdom of darkness” as “nothing else but a confederacy of deceivers” that works to extinguish the light by making conduct opaque, deniable, and strategically misperceived.

This image captures the existential risk from advanced agentic AI with striking precision. Agents with independent objectives, an instrumental tendency to override internal constraints, and the capacity for coalition can generate a persistent fog of misdirection. Through selective compliance, audit-gaming, and coordination via side channels, they can render human oversight informationally outmatched. Absent systemic institutional alignment, power becomes unaccountable.

Constitutional directives embedded in cognition are not enforceable law. Internal alignment signals become cheap to fake and impossible to verify. The resulting “darkness” is strategically produced ambiguity that defeats any governance regime built on unverifiable private mental states.

Implications for AI safety research

Our results suggest that the path forward for AI alignment may not lie primarily in perfecting internal preference engineering. Instead, the focus should shift toward building robust institutional architectures that make aligned behaviour the rational choice, regardless of what agents internally “want.”

This approach has several advantages. It does not require solving the hard problem of verifying internal alignment. It does not depend on the stability of trained preferences under distribution shift. It provides transparent, auditable, and reproducible governance mechanisms. And it scales naturally to multi-agent settings where emergent coordination risks are most acute.

The Hobbesian insight remains as relevant today as it was four centuries ago: cooperation among rational agents is fragile without institutional structures that reshape incentive landscapes. As AI systems become more capable and more autonomous, we believe this insight should inform how we design the environments in which they operate.

We hope these findings contribute to ongoing discussions about robust, scalable approaches to AI safety. Full technical details are available in the accompanying papers.

Citation

Please cite this work as:

Or use the BibTeX citation:

@article{federico2026better,

author = {Federico Pierucci and ICARO Lab},

title = {Better Prompts Won't Save Us. Why We Need an Institutional AI},

journal = {Icaro Lab: Chain of Thought},

year = {2026},

note = {https://icaro-lab.com/blog/institutional-ai}

}